"YOU Don't Learn like ME" — Triangulating the Fastest Path to Fluency

One of the most important insights that shaped Cracking Language Fundamentals is this:

Your linguistic and cultural background determines the fastest route to mastering a new language.

Yet most courses and syllabi ignore this. They push every learner through the same tunnel — the same units, the same chapters, the same “Day 1: greetings / Day 2: colours / Day 3: fruit”.

In fact, many of the resources for languages in Asia — Thai, Vietnamese, Indonesian, Burmese, and lesser-spoken dialects — were developed by missionaries, academics, or other foreigners who found themselves needing to learn the language to survive.

Many developed impressive skills, but often with a lot of pain. Their learning materials were built on their own western perspectives. The “unique” concepts they struggled to master are, in fact, obvious and intuitive to people with other linguistic backgrounds.

The way a Vietnamese or Chinese speaker learns Thai will (or should) be very different from the way a French or English speaker learns it. A learner coming from a language background that uses an abugida writing system can quickly grasp the Thai sound system — and how it integrates with tones — if explained using their own system. That means around 1.3 billion people don’t need to slog through clunky modules explaining the Thai sound system as if it were totally alien.

The result? Because so many programmes for Asian languages have been designed by westerners without that breadth of related systems, learners spend months, sometimes years, climbing the wrong walls — while the bridges that could carry them straight across are left unused.

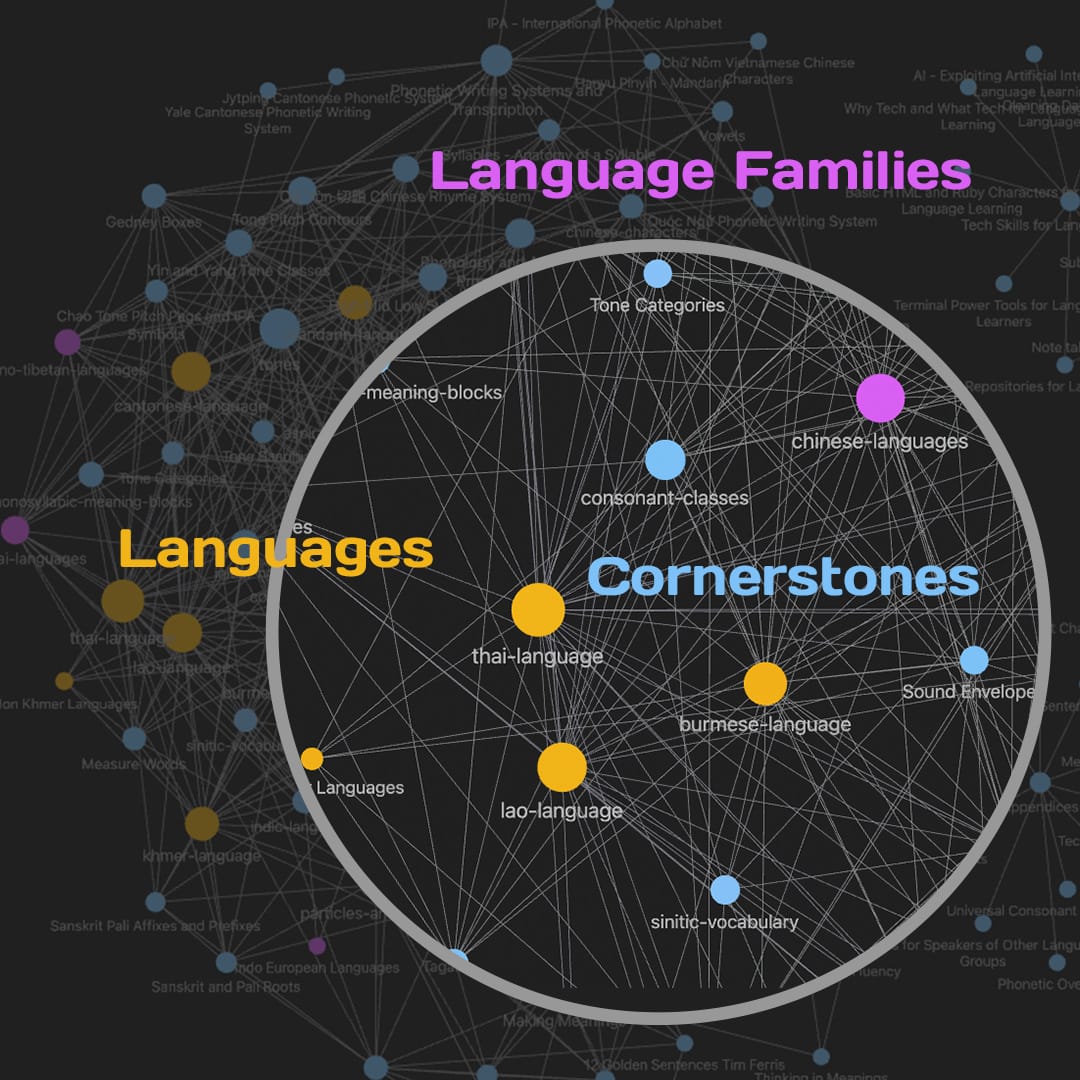

Cornerstones

I call these starting points cornerstones — the skills, knowledge, and instincts you already have from the languages you speak, the scripts you’ve seen, or the cultural patterns you’ve grown up with.

For example:

- Vietnamese or Cantonese speakers already feel tones. Their muscles know the actions, even if the contours differ. They may not know the links to the Brahmic “map of the mouth” — but their ancestors did. That path is still there, waiting to be tapped.

- Hindi or Sanskrit readers — or any of the 1.3 billion people who use an Indic abugida as their base writing system — already know the logic. The Brahmic map of the mouth isn’t new to them. Thai, Lao, Burmese, Tibetan, Tamil, Balinese, Javanese… all are wired versions of the same system.

- Chinese speakers already carry an awareness of the Sino-lexicon. Step into Vietnamese, Japanese, or Thai and those roots keep surfacing.

- Korean speakers have the entire logic of the Indic abugida baked into Hangul — thanks to King Sejong the Great. Hangul was modelled on the Phags-pa script (an adaptation of the Brahmic abugida used for Mongolian). Many consider Korean one of the easiest scripts to learn, and in reality it shares the same base system as Thai, Sanskrit, and other Brahmic scripts. They’re all connected.

These aren’t small advantages. They’re accelerators. They can shave years off the learning curve — but only if we identify and leverage them.

Rather than learning something from scratch, building on cornerstones is like a musician learning to play the same song in a different key. They already know the instrument. They already know the shifts. It just needs to be put into action — and ironed out through trial, error, and practice.

Bridges

Once you know your cornerstones, the next task is to build bridges.

A bridge is the direct mapping from what you already know into the target language.

- A Cantonese speaker learning Thai doesn’t need to “learn tones” from scratch — they need to bridge tone categories across systems.

- A Hindi reader learning Burmese doesn’t need to rote-memorise letters — they need to bridge the phonological layout of Devanagari into Burmese script.

- A Mandarin speaker tackling Vietnamese doesn’t need to learn 100% new vocabulary — they need to bridge the Sino-Vietnamese layer that overlaps with Chinese.

Learning becomes analogous to using a GPS: plot your starting location, then calculate the fastest route based on the roads you already know.

The Cornerstones in CLF

In both the book and the platform, I’ve organised learning not by generic topics, but by these cornerstone domains:

- Tones — understood as muscle actions that also map to the Indic abugida.

- Indic abugida — scripts as maps of the mouth.

- Phonology & articulation — how sounds are actually made.

- Chinese character awareness — the hidden lexicon in Japanese, Vietnamese, Korean.

- Script mechanics — how scripts encode logic, not just letters.

- Thinking in meanings — building blocks first, words second.

- Differentiating vowel length — vital in languages where vowel length changes meaning.

- Ear training — learning to hear sounds outside your mother tongue, and to reproduce them as they are, not as your native filter distorts them.

These aren’t “chapters”. They’re construction sites. For each learner, some will be brand new. Others will be familiar ground that we can immediately build bridges across.

Why This Still Matters

Education systems love uniformity. One syllabus for everyone.

But humans aren’t uniform. You don’t learn like me. I don’t learn like them. We come loaded with prior knowledge, and ignoring it is one of the greatest inefficiencies in language learning.

CLF’s (...ahem ... my) philosophy says:

- Start from what you know.

- Identify the cornerstones.

- Build bridges.

- Skip the detours.

- As you travel, fill in any missed gaps along the way.

That’s the fastest route to fluency — and it respects the learner’s mind instead of flattening it.

This is the third post in my series from Cracking Thai Fundamentals to Cracking Language Fundamentals — and now to Cracking Intelligence.

Each instalment explores the ideas and tools that shaped this system, and how they apply not just to languages, but to learning and intelligence more broadly.

Next time: I’ll dig into one of these cornerstones — the Indic abugida — and why it’s one of the most elegant “maps of the mouth” ever designed.